By Rohini Achal

Nature and Health Policy Intern, Summer 2023

This summer, I had the opportunity to intern for University of Washington’s (UW) EarthLab, an institute that collaborates with community to develop innovative, just, and equitable solutions to environmental challenges. One of EarthLab’s mainstay programs is their undergraduate summer internship experience, which is a cohort-based program that supports professional development and community-engaged work. Undergraduates are placed within one of EarthLab’s member or partner organizations for a 9-week internship focused on transdisciplinary and/or community-engaged research in a variety of contexts.

My fellow intern Amy Flores and I were placed at Nature and Health, an EarthLab member organization focused on exploring the relationship between nature contact and positive health benefits. This specific internship focused on identifying opportunities for Nature & Health to support local and state policy changes. As part of our work, Amy and I synthesized literature, interviewed public and private sector stakeholders, and conducted policy research. For our final project, we created a document for Nature and Health’s steering committee: a menu/manual of policy strategies and opportunities for involvement at the state and local levels.

These last nine weeks interning as a Nature and Health Policy Intern at UW EarthLab have brought with it immense joy and complex struggles. Between cohort meetings, speakers, reading, interviews, and research, I would like to express my gratitude for this experience by reflecting on nine things I learned over nine weeks at EarthLab:

1. Professional presence involves approaching every experience with set goals.

Though it may seem simple, the goal of an internship is to learn new things, and interns shouldn’t be expected to know everything coming in. Internships provide the opportunity to learn in and experience a professional setting. It is important to come in with curiosity and humility, as well as a recognition that not knowing something is not a weakness. This often involves setting SMART goals, something that we as students hear often, but that needs to be reinforced in an internship setting. Even if not explicitly required to outline SMART goals, an intern should make every effort to set out at least one or two goals and some objectives that can help them achieve those goals over the span of the internship. This can help keep the bigger picture in mind while also setting tangible goals to achieve that contribute towards the final goal or project.

2. Focus on one thing at a time.

I have found that I can often get ahead of myself with projects that excite me, which also increases my chances of making mistakes. Thinking about the big picture is exciting, often more enticing than the smaller steps it takes to achieve the big goal. However, breaking up large projects into smaller goals helped me promote intentionality with my work. Everything comes together in the end, and even if it is small, it can make a significant difference. Breaking things up and taking small bites of an otherwise quite large dish can make all the difference in successfully advancing goals related to any job position.

3. “Communities are neither inter- nor intra-homogenous.” – Mike Chang, Director of Equity at Cascadia Consulting.

Keeping in mind that communities do not require nor desire blanketed, single-focus solutions is important in every field. In public health, we like to talk about the social determinants of health, and sometimes can forget that intersectionality is a crucial component of heterogeneity. What works for one individual or even one community does not necessarily work for another, similar person or group. We all have intersectional identities that shape how we view the world and how we can frame solutions. This can get complex, but it is critical for us to remember as we move towards equity and justice in our programs, policies, and perspectives.

For the first four weeks of our internship, Amy and I spent hours combing through the scientific literature and researching policies in Washington, Oregon, California, Utah, and New York. At the end of Week 3, we brainstormed candidates to interview who had specific insights into policy work focusing on nature contact and human health. By Week 4, we had our interview questions and had emailed more than a dozen potential candidates for informational interviews. We were also diving into more climate-specific topics in our weekly cohort meetings.

4. Agricultural sustainability was inherently practiced by Native and Indigenous communities of the Americas and of other nations.

In Robin Wall Kimmerer ‘s book Braiding Sweetgrass, she writes, “The traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous harvesters is rich in prescriptions for sustainability.” Now, these same agricultural practices, such as whaling and fishing, are viewed as unethical.

After watching the movie “Gather” and reflecting on Traditional Ecological Knowledge, food systems and food sovereignty, the first thought that came to mind was the lack of respect that the scientific community has for Indigenous ways of knowing. For centuries, Indigenous communities have had reciprocal relationships with natural resources. Indigenous peoples’ agricultural, spiritual, and cultural practices were interdependent of the mutual caretaking that the land, peoples, and animals share for one another. Relationships with the earth were formed on reciprocity and connection instead of extraction. Sustainability was interwoven with all practices undertaken by Indigenous peoples, especially in comparison to our current capitalist resource extraction models.

Weeks 5-8 were where I really saw a shift in the work that we were doing at Nature and Health. Amy and I had spent the past four weeks doing primary and secondary literature reviews, trying to tease out and quantify the learnings of researchers investigating the relationships between nature exposure and human health.

Between Weeks 5-8, we were able to interview 14 (n=12 interviews) representatives from governmental agencies, community-based organizations, non-profits, and private sector businesses. Each representative engaged in environmental justice policy or advocacy work, and each shared some amazing insights from their specific projects and strategies that they used to mobilize community and garner support. To our surprise, people were extremely willing and excited to hear about our project and to discuss the work that they were doing in their organizations. They highlighted that we, as interns, gave them hope for the future of environmental justice and climate action work.

5. Climate grief is real, and it is critically important to “highlight successes and places of joy. We are still entitled to joy, even when we are fighting.” – Jamie Stroble, Director of Climate Action & Resilience at The Nature Conservancy (Washington)

During our week 5 cohort meeting, our guest Jamie Stroble shared that combatting climate grief can be extremely difficult when working in climate and environmental justice jobs. She shared that “Nothing is Forever,” and that we should highlight places of joy in projects, careers, or job opportunities that we may not be necessarily elated about. Each job offers a different skill set and provides a talking point for the rest of your career. From this internship, the main talking point I will be carrying forward is the importance of concise science communication as a way to empower potential community and public sector partners.

6. It is just as important to “focus on the good as it is on the bad when talking about environmental justice.” – Jon Snyder, Senior Policy Advisor to Jay Inslee

Jon Snyder shared the wonderful insight that as policymakers and researchers, we tend to focus on the “bad” side of environmental justice: air and water pollution, lack of food sovereignty, urban heat islands, and green gentrification. In doing so, we forget to see what’s on the other side of the coin – the good that we are doing and that we can still do.

It is feasible and within reach to figure out how to provide communities with culturally relevant parks and greenspaces; researching the types of trees and planting those that offer maximum health benefits for communities; and how to reduce carbon emissions with simple solutions, like electrifying and expanding access to public transportation. Focusing on the tangible solutions and on trying to maximize the benefits with each interdisciplinary solution is where we need to put our funds.

Moving into Week 7, we started to plan our final project, which we identified to be policy brief/internal document of sorts, roughly describing 1) the “lay of the land” related to local and state policy; 2) what other local and state organizations are doing, both advocacy and policy-wise; and 3) identifying areas that Nature and Health could get involved in in the future.

7. “Treat every internship position as a demonstration that you can be a great employee.” – Chas Jones, Program Manager of Climate Resilience at the Affiliated Tribes of the Northwest Indians (ATNI)

On Week 7, we had the pleasure of meeting Chas Jones and Kylie Avery as representatives from the Affiliated Tribes of the Northwest Indians (ATNI). They discussed their career path and their jobs with ATNI, and then opened the floor up to questions and suggestions. Chas specifically stressed the idea that as a manager, he is looking and treating every intern as a future employee. An internship is an opportunity to demonstrate your current skills and an even bigger opportunity to gain experience and grow as a potential employee. Framing every internship as a learning opportunity and a time to highlight your skills to your supervisor(s) should be at the forefront of every internship.

8. Always try define the “so what” when communicating your work to others.

During Week 8, we had a visit from the Senior Director for Marketing and Communications at the UW College of the Environment, John Meyer. He shared three tips that are useful to keep in mind for science communications, but that are important to keep in mind for communications in any medium: (1) define your goal; (2) know your audience; and (3) craft your message. The main takeaway from John’s presentation for me was about the “so what” of your message. The “so what” – the bottom line – of the results and the data trends will vary depending on the audience. Legislators are looking at a problem and its potential solutions in a different way from business owners and even different still from nonprofits.

All of these learnings were important for our final internship project, which for me was a “reference report” that we created for the Nature and Health internal steering committee. It is comprised of researchers and scientists, and thus it was not essential for us to recap the findings of the literature, but instead was important to get right to the suggested policy tools that Nature and Health can utilize. Another important thing to get across was summarizing our learnings from the various stakeholders we interviewed.

9. “Action is hope. There is no hope without action” – Ray Bradburry

On Week 9, McKenna Parnes came into our cohort group to speak about Climate Grief and her research on Climate Anxiety, a familiar topic for all. As a group, we echoed frustrations with the lack of policy work addressing climate change as well as how the burden to create climate solutions falls on youth (us), even though we didn’t create the problem. A topic that was of particular interest to me was how to mediate climate anxiety and grief while highlighting important and effective actions we have taken to combat climate change. McKenna shared that in her study, collective climate action was a mediator of the relationship between experiencing depressive symptoms and having high climate anxiety. The more people participate in collective action, the greater the reduction in experiences of depressive symptoms.

McKenna shared that it’s often a tradeoff of experiencing grief while trying to highlight hope. She shared a quote by Ray Bradburry: “Action is hope. There is no hope without action.” We are (slowly) moving the needle on climate change action and mitigation. We need to rapidly accelerate the many strategies that we have already started to implement, and approach everything with a systems approach. There is hope even in a topic so complex and challenging as climate change.

I am excited to see what is next for me and to take on my final year at the University of Washington. My biggest learning from this experience is that I actually am interested in research – but policy research, not scientific research in a stereotypical lab. I also have realized that career paths are not linear and that there are so many skills that I have gained from this internship that can be applied to a variety of jobs.

I would like to express my sincerest thanks to Amy Flores for being an amazing co-worker and to Allie Long for helping me write this blog. Thank you to everyone else in EarthLab’s 2023 intern cohort, you all have been a pleasure to work with and to get to know. Thanks to Carly Gray and Josh Lawler for being fabulous supervisors and supporting us in this journey. I would also like to thank all of the speakers that came to our cohort meetings to share their journeys as well as all the interviewees that were willing to talk to Amy and me for this project. Thank you!

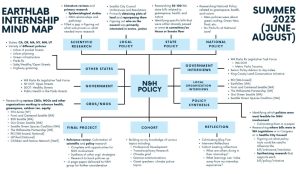

Here is a visual representation of the work that I did in this internship:

Introducing NextGen Narratives, a fresh addition to the EarthLab news page, tailored for University of Washington students to express how they’re thinking about taking equitable climate action in a variety of ways. If you’re a student eager to join NextGen Narratives, don’t hesitate to contact Allie Long, EarthLab’s Communications Lead, at alongs@uw.edu.